You don’t get much more Australian than the beloved wombat. These short, stocky marsupials are emblematic of Australia’s unique wildlife. Although the common wombat (Vombatus ursinus) is the most well-known, there are two other species, the Southern Hairy Nosed Wombat (Lasiorhinus latifrons) and the Northern Hairy Nosed Wombat (Lasiorhinus krefftii). There is very little physical difference between the species but as the names suggest, the hairy nosed species have more noticeably hairy snouts than the common wombat.

The Common Wombat (image from Animalia.Bio)

The Southern Hairy Nosed Wombat (image from Animalia.Bio)

Evolutionary History and Taxonomy

Generally, the evolution of the wombat we see today is poorly understood. Koalas and wombats are in the same clade, called the Vombatiformes, of which they are the only surviving members. This clade is part of the order Diprodontia, with the sister order Phalangerida containing other iconic Australian wildlife like the possums, wallabies, kangaroos and rat kangaroos.

The Diprodontia were once a very diverse order, with large tapir like wombat relatives and so-called marsupial lions roaming the earth. However, during that time of great change, the Pleistocene Epoch, there were massive extinctions of many species, but especially in the Diprodontia, including the Diprotodon, a giant wombat weighing up to 2700 kg and growing to as large as 4 metres!

A replica of the Diprotodon in the Australian Museum

The lack of wombat evolution knowledge is partly attributed to the constantly growing molars of modern wombats, which makes it particularly tricky to link them back to the fossil record. On top of this, most of the fossil record discovered for this species is very early, with few intermediate fossils found. But in 2020, a new paper was published that has shed some light on the mystery. In the Lake Eyre Basin in North-eastern Australia, scientists discovered a partial skull and lower jaw that allowed them to determine the intermediate species between those earliest wombat relatives, called the wynyardiids, and the cute little bumbling marsupials we see today. This species was named Murkupina nambensis and is estimated to have been 5 times the size of the wombats today, and it was from these early relatives that modern species developed their specialised digging abilities.

Range and habitat

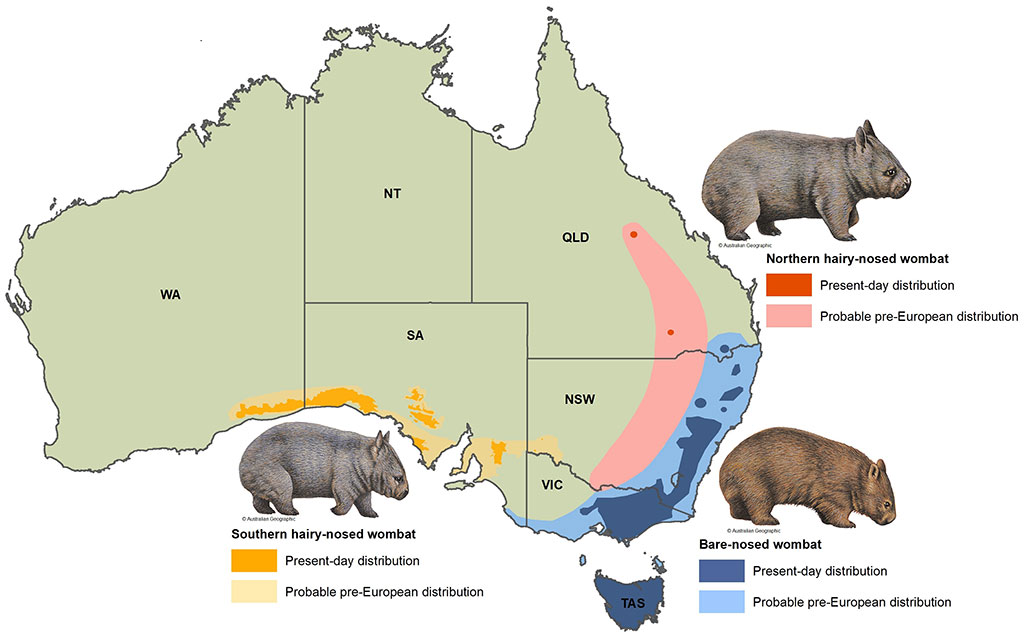

The three species of wombat in Australia have slightly different ranges:

- The common wombat has three distinct identified populations; one in South-eastern Australia, one in Tazmania and one in Flinders Island (a small island between Australia and Tazmania). Although considered common and population trends are seen as stable, there has been significant reduction in habitat since European arrival continuing to this day that puts this species at risk of genetic isolation of populations as connecting habitat is lost.

- The Southern Hairy Nosed Wombat is found patchily distributed throughout New South Wales and into Western Australia.

- The Northern Hairy Nosed Wombat, the most endangered of all three, is located only in two small, intensively managed populations in Epping Forest National Park and Richard Underwood Nature Reserve.

Generally, all wombats inhabit a range of ecosystems from temperate, eucalypt woodlands through to grasslands and semi-arid scrub. Unfortunately, all of these habitats are under intense threat from worsening forest fires, land use change and deforestation.

Dig for victory: burrowing wombats

One of the most well-known aspects of wombat ecology is their extensive burrows which they excavate with their powerful back legs. They are so well adapted to burrowing that even the pouches for their young face backwards so that the burrowing mothers don’t cover their young with dirt! These large warrens often have multiple wombats living in there at once and have even been known to be home to other species! In the devastating forest fires of January 2020, the warrens were used by several other species fleeing the inferno above for the thermostable conditions underground. Recently, scientists developed a new tool to investigate these vast underground networks called the WOMBOT, a remote controlled, all terrain robot that can move through warrens with minimal intrusion to the wombats. Researchers are hoping to utilize this technology even more in coming years to better understand wombat behaviour and ecology, as they spend the vast majority of their time in them. Outside of the burrows, they spend most of their time foraging and are generally solitary outside of the breeding season.

Another unique feature of the wombat is their cube shaped poop! Yes, that’s right, wombats’ poo stackable cubes of poop that they use to mark their territories and attract mates; quite literally stacking them like a smelly jenga tower. This has so intrigued researchers that recently a post-doctoral researcher in mechanical engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology carried out a study on wombat physiology to better understand this phenomenon. Wombats unfortunately killed in road traffic accidents were donated to the study and their intestines dissected; it was discovered that a portion of the wombat intestine is deformed, allowing their cube shaped poop to form.

Wombat conservation: not so common?

Although the common wombat is assessed by the IUCN to be of Least Concern, many biologists are still concerned about the future of the species and stress that many species that are considered common slip into quiet population declines towards extinction under the noses of conservationists. Australia is one of the worst developed countries in the world for extensive deforestation and logging, with only 50% of native forest remaining intact and is classed as having one of the highest rates of mammal extinction of any continent. On top of these pressures, wombats are also considered a nuisance by farmers, who will use lethal control to prevent them destroying crops and use explosives on their burrows to stop them disrupting fences and allowing dingoes into agricultural land. On top of this, there are increasing rates of mortality from road traffic accidents. This is slowly driving the species into increasingly more isolated patches, running the risk of genetic drift and inbreeding in these isolated populations.

All species of wombat, along with many other mammals, face a significant threat from the small but mighty mange mite. These common arthropods spread sarcoptic mange, a disease that causes alopecia, crusty skin, reduced sensory perception and behavioural alterations. Its even thought that mange can limit gonad activity of wombats, thus affecting their reproduction. Studies of infected wombats show they spend huge amounts of their time scratching instead of foraging or resting, leaving them with very poor body condition. Although the full range of mange impacts are still poorly understood, severe prolonged infections can lead to mortality, especially during long droughts, when wombats spend more time tending to their irritating itches and not enough on finding food and water. Burrows are likely to be the hub of mange infection, and with increases in environmental temperatures, wombats are likely to spend more and more time in these thermostable warrens, increasing the chance of mite transmission.

Despite the seemingly comfortable status of the common wombat, the picture is not so rosy for the Southern Hairy Nosed Wombat. Classed by the IUCN red list as Near Threatened, huge stretches of their habitat are being converted into agricultural land, removing their food supplies, and destroying good burrow habitat. In this reduced habitat, there is increasing competition with livestock and introduced, invasive species for food supplies and space, driving even more conflict with farmers.

For the Northern Hairy Nosed Wombat, the picture is even more bleak. This species exists only in two small managed populations in Epping Forest and Richard Underwood Nature Reserve. Through the 1980’s their numbers dropped as low as 30-40 individuals, driven by huge scale habitat destruction and severe droughts in their range. This left them vulnerable to local environmental catastrophes and the health risks of inbreeding, which they are still suffering from today. This led to the Department for Environment and Science (DES) taking over the management of this struggling species and moving them into the Epping Forest Reserve, a 2750-hectare space of eucalypt woodland which is perfect wombat habitat, with plenty of healthy grasses for food and loamy soils for burrowing. At the last census in 2016, there were 245 individuals with roughly 50% females and males. In 2008, conservationists grew concerned that all members of the species were in one place, especially in the face of increasing wildfires, droughts, and floods; there was a real chance one bad year could wipe the entire species out. The decision was taken in 2008 to translocate 15 wombats to a new a protected area and scientists began scouring the area for suitable habitat. They found the perfect place in the Yarran Downs in New South Wales. The habitat was in really good shape, largely thanks to the previous owners, the Dennis family, who had gone to great lengths to manage the land. The owners at the time, Ed and Gabriele Underwood entered into an agreement to turn their land into the Underwood Nature Reserve, preventing potential development by energy companies and giving nature a space to thrive. A cattle exclusion fence was built around the land, especially important for wombats as cattle frequently destroy burrows and outcompete wombats for food. A small but thriving colony of wombats now lives here, supported by a dedicated team of scientists and volunteers.

But measures are in place to save the wombats from a slow slide towards extinction, especially for the critically endangered Northern Hairy Nosed Wombat. In Epping Forest and the Underwood Nature Reserve, a team of conservationists, land managers and volunteers work tirelessly to protect the species. The wombats are protected under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act of 1999, which means government intervention and funding support are provided. Population management in these reserves involves a range of activities including:

- Maintaining good wombat habitat: through controlled burns, removal of invasive weeds and flood prevention.

- Mitigating and removing threats: ensuring the integrity of the cattle exclusion fence, removing invasive species such as feral goats and pigs that outcompete the wombats for food.

- Breeding of the species with genetic testing to ensure the best genetic diversity possible, especially important in the Northern Hairy Nosed Wombat, which has suffered fast, precipitous declines.

- Researching behaviour and ecology to better inform conservation interventions.

- Population monitoring through camera trapping, trapping of live individuals for health checks and burrow inspections.

- Wombats in these protected areas are also given supplementary feed and water stations.

You can read more about the governments plan at https://www.qld.gov.au/environment/plants-animals/conservation/threatened-wildlife/threatened-species/featured-projects/northern-hairy-nosed-wombat/conservation.

For the Southern Hairy Nosed Wombat there is unfortunately no formal recovery plan in place, despite there being known concerns about inbreeding. However, although there is no official government intervention like there is for the Northern species, Adelaide Zoo works closely with farming communities to reduce conflicts by managing the disruptions wombats cause to farmers crops and fences. More recently, the New South Wales Office of Environment and Heritage set out an action statement for the conservation of the Southern Hairy Nosed Wombat, involving incentivising locals to disclose wombats on their land, protecting warrens from livestock disruption and carrying out monitoring in these areas. They are also aiming to set up more genetic studies to fully assess the levels of inbreeding.

Wombats are no doubt some of the cutest marsupials in Australia, but their importance goes beyond their chubby bodies and sweet faces. They are excellent ecosystem engineers through grazing, keeping plants at manageable levels. Through their extensive burrows and the digging that creates them, they cause huge turnover of soil, ensuring essential nutrients are well distributed. Fortunately, it seems there is political will and resources to save the Northern Hairy Nosed Wombat from extinction, to bring the Southern Hairy Nosed Wombat numbers up and to safeguard the future of the common wombat through close monitoring.

Conservation heroes!

- The Wombat Awareness Organisation is a charity set up to rescue, rehabilitate, and raise awareness of wombats, both in the wild and in zoos. They have a wombat sanctuary where rescued wombats can recover and have a 24-hour emergency helpline. You can help them out by donating to help fund their vital work, or if you live in the area you can visit the sanctuary and even volunteer with the wombats, feeding wild wombats, keeping their habitat safe and helping raise funds and awareness. You can also adopt one of their wombats too!

https://www.wombatprotection.org.au

The Wombat Protection Society of Australia is another not for profit organisation that aims to raise money and awareness to immediately protect wombats from hard. They also conduct research on the biology and ecology of wombats, and they have a particular interest in the mitigation of threats faced by wombats, particularly including the threat from sarcoptic mange. You can donate or become a member of the society and fund their vital work.

Awesome videos!

References

Beck, R.M.D. Louys, J. Brewer, P. Archer, M. Black, K.H. and Tedford, R.H. (2020) ‘A new family of diprotodontian marsupials from the latest oligocene of Australia and the evolution of wombats, koalas and their relatives (Vombatiformes)’ Nature, 10, pp 1-13

Evans, M.C. (2007) ‘Home range, burrow-use and activity patterns in common wombats (Vombatus ursinus) Wildlife Research, 35(5), pp 455-462

https://www.bushheritage.org.au/species/wombats

https://www.britannica.com/animal/Diprotodon

https://ielc.libguides.com/sdzg/factsheets/wombats/behavior

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2018/nov/18/scientists-unravel-secret-of-cube-shaped-wombat-faeces

https://www.wilderness.org.au/news-events/10-facts-about-deforestation-in-australia

Roger, E. Laffan, S.W. and Ramp, D. (2007) ‘Habitat selection by the common wombat (Vombatus ursinus) in disturbed environments: implications for the conservation of a common species.’ Biological Conservation

Roger, E. Laffan, S.W. and Ramp, D. (2010) ‘Road impacts a tipping point for wildlife populations in threatened landscapes.’ Population Ecology, 53(1), pp 215-227

Ross, R. Carver, S. Browne, E. and Son Thai, B. (2021) ‘WomBot: an exploratory robot for monitoring wombat burrows.’ SN Applied Sciences, 3 pp 1-10

Simpson, K. Johnson, C.N. and Carver, S. (2016) ‘Sarcoptes scabei: the mange mite with mighty effects on the Common Wombat (Vombatus ursinus)’ PLoS One, 4(11)

Taylor, R.J. (1993) ‘Observations on the behaviour and ecology of the common wombat.’ Australian Mammalogy, 16(1), pp 1-7