Babirusa

The Sulawesi Babirusa (image from https://animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/babirusa)

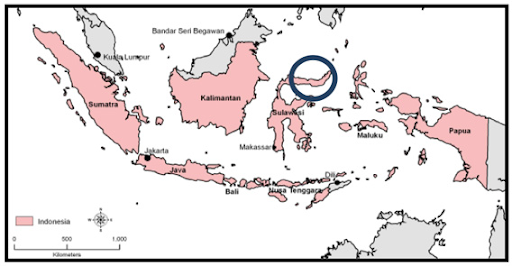

Found only in the Indonesian Islands of Sulawesi, Togian, Sula and Bura, the babirusa, or ‘deer-pig’ in the Malay language, are a genus, Babyrousa, of small pigs with characteristic upwards curving canine tusks. Despite much pondering, no one actually knows the purpose for these dramatic tusks; some suggested the males use them to clear foliage away for the tusk challenged females, but since females are frequently seen travelling alone, this seems unlikely. Others suggested perhaps they were used in fighting but field photography of males tussling shows that they stand on their hind legs and ‘box’ with their front legs. Maybe the males are the equivalent of a peacocks glorious tail feathers; a clear signal of genetic fitness to any female who’s looking for her next romantic entanglement. The males only have the upper tusks, but both sexes have the lower tusks that protrude upwards, peeking out of their mouths. If the tusks have a consistent blood supply and they don’t get broken off in a tussle with another male, the tusks will continue to grow and curve backwards, piercing the skin and growing up to 12 inches! Imagine that headache!

Male Sulawesi Babirusa boxing (Image from https://news.mongabay.com/2010/12/saving-sulawesis-pig-deer-the-babirusa/)

So distinctive is the appearance of this pig that in Indonesian culture, demonic masks are made based off the Babirusa and their almost prehistoric tusks. Raksasas are demonic Hindu demigods, and their faces, distinctly Babirusa-like, line the walls and ceilings of the Kertha Gosa pavilion in Bali, a palace built in the 1600’s. Not only do their faces make an appearance in these important cultural places, but the Babirusa also play a role in Indonesian myths and legends. They are said to hang upside down from trees during the night and hook their tusks over branches to support their heads. Many local people believe the Babirusa is nothing more than a myth; they are so elusive that even those who live close to their rainforest homes never see them.

There are three species existing today:

- The Hairy Babirusa (Babyrousa babyrousa)

- Sulawesi Babirusa (Babyrousa celebensis)

- Togian Island Babirusa (Babyrousa togeanensis)

The Hairy and Sulawesi Babirusa are classed as vulnerable by the IUCN red list, with declining population trends. The Togian Island Babirusa is now assessed as endangered with a fragmented population confined to just the Togian Archipelago.

An example of a Balinese Raksasa mask, inspired by the dramatic tusks of the Babirusa. (image from https://acadiaworldtraders.net/)

Shy Swine Snuffling in the Sulawesi Forest

Babirusa inhabit the swampy parts of rainforests in the Islands of Indonesia, specifically Sulawesi, Togian, Sula and Bura, and nowhere else in the world. Like many pigs, Babirusa are not fussy eaters and will chow down on a range of food from fruits, leaves, mushrooms, bark, fish, insects and even small mammals. They are also partial to a fruit cocktail of many cultivated crop plants, like mango, cassava and papaya. They exhibit the classic rooting behaviour of so many of their swine counterparts, snuffling around and turning over soil, sand and soft mud to dig up their dinner. Troops of Babirusa have been observed wallowing in mud baths and using communal volcanic salt licks.

The Hairy and Sulawesi Babirusa are listed as vulnerable on the IUCN red list, with the Togian Islands Babirusa classed as endangered, in large part due to its tiny range. The Indonesian islands were colonised sometime around 30,000 years ago, and studies of the prehistoric remains of early humans show evidence of Babirusa in settlements, indicating they were once part of a standard human diet. This was all fine and pretty sustainable, as so many early hunter gatherer societies were, but in modern times when clear cutting forest became a standard practice, this changed the game entirely for this shy pig. Throughout the 1980s and 90s, despite the legal protection in place, thousands upon thousands of babirusa were killed for their meat in the main to supply markets in the Northern parts of the Island. As the Babirusa is hunted to local extinction in one area, hunters simply move on and sell the Babirusa there to the more profitable markets in the North, rather than eat the pigs themselves as part of their subsistence living. Unfortunately, many babirusa are snared in traps set out for the Anoa, a small species of wild cattle also called the dwarf buffalo. Many local Muslim hunters will not eat pig due to their religious beliefs, and sadly those Babirusa caught in their traps will be left to rot. In some of the coastal regions of the island, there are reports that Babirusa are deliberately trapped purely for the purpose of having their teeth removed for the Bali mask making trade. This is an important part of Balinese culture, as they believe they are creating spiritual homes for their ancestral spirits and gods to reside in, but possibly alternative resources could be considered in the future to prevent further pressure on Babirusa populations already pushed to the edge.

Like so many species in the Indonesian region, deforestation is a massive issue for the Babirusa. Not only does it make what was once impenetrable forest accessible to poachers, it also removes vital habitat for troops of Babirusa who need space to breed and forage. Although Sulawesi has several large nature reserves, they are not large enough to cover the home range of a herd. They are also extremely geographically isolated from each other, meaning there is no chance Babirusa from across Sulawesi can interbreed and preserve their genetic integrity. Wildlife corridors have been suggested to connect these reserves and allow intermingling of Babirusa herds, but this is a complicated issue that must consider the needs of locals who live around these reserves, including the many farmers who need land to earn a living.

Conservation optimism

https://www.actionindonesiagsmp.org/

Set up in 2016, Action Indonesia are a collection of over 50 organisations across Europe, America, Asia, Indonesia, America and Canada that are collaborating to develop conservation strategies to save iconic Indonesia wildlife, in particular the Banteng, Anoa and Babirusa. They are a GSMP, or Global Species Management Plan. Overseen by the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA) they involve zoos, governments, and conservation organisations to utilise the varied skills of people from these places to develop an effective long term conservation plan.

Their plan consists of 4 main objectives:

- To reach a demographically healthy and genetically healthy global ex situ population.

- To raise awareness among zoo visitors.

- To use zoo expertise to help in situ conservation.

- To prioritize and support in situ projects.

Babirusa are protected under the Indonesian Law Act of 1990 concerning the Conservation of Living Resources and Their Ecosystems. In 2013, the government also released a conservation strategy involving the identification of 11 priority conservation sites. Currently they reside in 6 protected national reserves that are patrolled by rangers who run anti-poaching brigades and rehabilitate injured Babirusa. There is also increasing public awareness campaigns run in local schools and businesses to engage communities in their conservation plans. Action Indonesia also carry out numerous camera trap studies and population monitoring combined with faecal analysis techniques to improve estimates of numbers in the wild. Alongside several zoos such as Chester Zoo in the UK Action Indonesia are running a global captive breeding programme to maintain an insurance population of healthy and genetically diverse Babirusa. A studbook, a registry of all captive individuals and their births, death, parentage, and transfers, is held by Opel Zoo in Germany for the captive Babirusa population. Zoo experts will also often travel to Indonesia to work with rangers and local communities to promote Babirusa conservation.

2 North Sulawesi Babirusa piglets born recently at Brevard Zoo in Melbourne, Florida, as part of their captive breeding programme (Image from https://www.zooborns.com/zooborns/2022/06/north-sulawesi-babirusa-piglets-make-first-visits-to-habitat.html)

Awesome videos!

A video from the Simthsonian channel highlighting the amazing tusks of the male Babirusa.

A look into the mysterious ‘pig-deer’ of Indonesia.

References

Burton, J. Bailey, C. Yonathan, Y. Andrews, J. Chandra, I. Forys, J. Fitzpatrick, M. Frantz, L. Mustari, A.H. Holland, J. Hornsey, T. Humphreys, A. Hvilsom, C. Leus, K. Metzler, S. Pentawati, S. Rode-Margono, E.J. Rowlands, T. Semiadi, G. Smith, C. Sumampau, T. Traylor-Holzer, K. Tri Hastuti, Y. Tumbelaka, L. and Young, S. (2020) ‘Progress of the Action Indonesia GSMPs 2016-2020: Global collaboration to conserve the anoa, banteng, babirusa and Sumatran tiger.’ Research and Reports.

Clayton, L. and MacDonald, D.W. ‘Social organisation of the Babirusa and their use of salt licks in Sulawesi, Indonesia.’ Journal of Mammalogy.

https://blog.nature.org/science/2014/02/11/babirusa-conserving-the-bizarre-pig-of-the-sulawesi-forest/

https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/136472/44143172

https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/136446/44142964

https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/2461/9441445

Macdonald, A. (2005) ‘The conservation of the Babirusa.’

Milner-Gulnard, E.J. and Clayton, L. (2002) ‘The trade in Babirusas and wild pigs in North Sulawesi, Indonesia.’ Ecological Economics, 42(1-2)

Mustari, A.H. Burton, J. Basri, M. Soehartono, T.R. Kaniawati, S.C. Rejeki, I.S. Wheeler, P. and Semiadi, G. (2015) ‘Strategy and Action Plan for Conservation of Babirusa 2013-2022.’ Directorate of Conservation of Biodiversity.